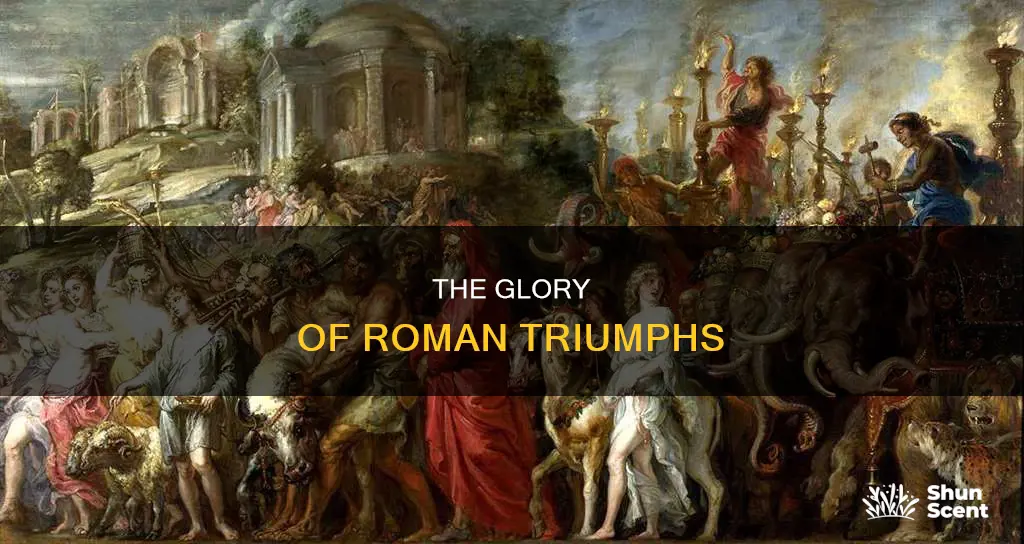

A Roman triumph was a civil ceremony and religious rite held to celebrate the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory. It was the highest honour bestowed upon a victorious general in the ancient Roman Republic and was the summit of a Roman aristocrat's career. The word 'triumph' probably comes from the Greek 'thriambos', the name of a procession honouring the god Bacchus. The ceremony began with a procession from the Triumphal Gate in the Campus Martius to the Temple of Jupiter on Capitol Hill, passing through the forum and the Via Sacra. The procession included the victorious general, who wore a laurel wreath and a gold-embroidered toga, riding in a chariot drawn by four horses, as well as musicians, sacrificial animals, spoils of war, and captured prisoners in chains. The general offered sacrifices to Jupiter at the temple, and the prisoners were usually slain. The ceremony concluded with a feast for the magistrates and Senate.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Purpose | To publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander |

| Participants | Military commander, Roman forces, captives, spoils of war |

| Clothing | Crown of laurel, all-purple gold-embroidered triumphal toga picta |

| Face | Painted red |

| Transport | Four-horse chariot |

| Route | Streets of Rome, ending at Jupiter's temple on Capitoline Hill |

| Offerings | Sacrifice and tokens of victory offered to Jupiter |

| Frequency | Rare after the Augustan settlement and the end of the fasti triumphales in 19 BCE |

| Popularity | Triumph was the summit of a Roman aristocrat's career |

| Procession | Senate, trumpeters, spoils of war, captives, white bulls for sacrifice, lictors, the imperator, his family, officers, troops |

What You'll Learn

The Roman triumph was a civil ceremony and religious rite

The Roman triumph was the summit of a Roman aristocrat's career and the highest honour bestowed upon a victorious general in the ancient Roman Republic. It was also a great honour that afforded the recipient great publicity and, therefore, popularity with the people of Rome.

The Roman triumph was a highly ritualised affair. The victorious general, or triumphator, wore a crown of laurel and an all-purple, gold-embroidered triumphal toga picta ("painted" toga), regalia that identified him as near-divine or near-kingly. In some accounts, his face was painted red, perhaps in imitation of Rome's highest and most powerful god, Jupiter. The general rode in a four-horse chariot through the streets of Rome in an unarmed procession with his army, captives, and the spoils of his war. The procession followed a fixed route, running from the Field of Mars down to the river Tiber, doubling back on itself to avoid an ancient bog, then through the Circus and along the Sacred Way (Via Sacra) to the Temple of Jupiter on Capitoline Hill. Here, the general offered sacrifice and the tokens of his victory to Jupiter.

The Roman triumph was also an opportunity for great festivity. The streets were cleaned in preparation, and arrangements were made for feasting and banquets after the triumph. There was also plenty of drinking by the Roman soldiers who played a part in the triumph of their general. The festivities also included music and singing, and there was a sweet smell in the air from the rose petals and other scented flowers strewn across the path of the triumphator.

Craft Beers: Sweet Aroma Science Explained

You may want to see also

It was the summit of a Roman aristocrat's career

A Roman triumph was a civil ceremony and religious rite held in the ancient city of Rome to celebrate a military victory. It was the highest honour bestowed upon a victorious military commander and was the summit of a Roman aristocrat's career.

The Roman triumph was a spectacular celebration parade, a great honour, and an opportunity for self-publicity. The victorious commander, or triumphator, was granted the privilege of wearing special regalia and riding a spectacular chariot pulled by four horses in a lavish procession through the streets of Rome. The regalia—a laurel crown, a purple and gold toga, and red boots—identified the triumphator as near-divine or near-kingly.

The triumphator's procession began at the Triumphal Gate in the Campus Martius and ended at the Temple of Jupiter on Capitoline Hill, where he offered sacrifices and tokens of victory to Jupiter. The procession included musicians, sacrificial animals, spoils of war, and captured prisoners. The triumphator's soldiers marched last, singing songs to ward off the jealousy of the gods and protect their commander.

The Roman triumph was granted and funded by the Senate, and the victorious commander was required to have been a magistrate cum imperio (holding supreme and independent command) who had won a major land or sea battle, killing at least 5,000 enemies and ending the war.

The ceremony also included a speech by the triumphator before the Senate, magistrates, his army, and the public, in which he praised his legions and gave out decorations and money. The triumph concluded with a banquet inside the temple for the VIP guests, and sometimes, in the late Republican period, a feast for the general populace.

Aromatherapy Physical Therapy: Healing Through Scents and Movement

You may want to see also

The procession included spoils, captives, and the victorious general

The Roman Triumph was a civil ceremony and religious rite held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory. The procession included spoils, captives, and the victorious general, known as the triumphator.

The procession began at the Campus Martius, where the troops gathered before the general. The triumphator entered Rome in a spectacular chariot drawn by four horses, wearing a purple and gold embroidered toga picta and a laurel wreath. Their face was painted red, perhaps in imitation of Jupiter, the Roman king of the gods.

The procession was led by the senate, trumpeters, and the captives, often in chains, followed by the spoils and treasures taken in war. The triumphator's personal bodyguards, known as lictors, accompanied him in the chariot. The triumphator's family, officers, troops, and unarmed soldiers followed behind. The procession was filled with rituals and symbolism, with priests offering incense and performing religious rites, and the soldiers singing and displaying captured enemy banners.

The procession followed a fixed route, passing through the Circus and along the Sacred Way (Via Sacra) to the Temple of Jupiter on Capitoline Hill, where the triumphator offered sacrifices to the gods. The route was carefully planned to showcase the general's achievements and allow as many people as possible to witness the procession.

Vapor and Aroma: Understanding the Key Differences

You may want to see also

The general wore a laurel crown and a toga picta

The Roman triumph was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory. The general, or triumphator, wore a laurel crown and a toga picta ("painted" toga). This was a semi-circular piece of fabric, draped over the shoulders and around the body. The toga picta was dyed solid purple and decorated with gold thread or gold embroidery. It was worn over a tunica palmata, a tunic embroidered with palm leaves.

The triumphator's laurel crown and toga picta identified him as near-divine or near-kingly. In some accounts, his face was painted red, perhaps in imitation of Rome's highest and most powerful god, Jupiter. The triumphator's clothing also connected him to Rome's mythical and semi-mythical past. The purple and gold toga picta, laurel crown, red boots, and red-painted face were associated with the ancient Roman monarchy and the statue of Jupiter Capitolinus. The triumphator was, in effect, "king for a day".

The toga picta was considered ancient Rome's "national costume" and had great symbolic value. It was complex, costly, and uncomfortable to wear. It was reserved for ceremonial occasions and worn only by the highest classes. The triumphator's toga picta was distinct from the togas worn by other citizens, which were usually white. The toga picta was worn by generals in their triumphs, and during the Empire, it was also worn by consuls and emperors.

The triumphator's clothing was a significant part of the Roman triumph ceremony. The triumphator rode in a four-horse chariot through the streets of Rome in an unarmed procession with his army, captives, and the spoils of his war. The procession culminated at Jupiter's temple on Capitoline Hill, where the triumphator offered sacrifices and tokens of his victory to Jupiter. The triumphator's clothing, therefore, served to elevate him above every other Roman citizen during the ceremony, promoting him to a near-divine status.

Aromatic Massage: Benefits and Techniques

You may want to see also

The triumph concluded with sacrifices at the Temple of Jupiter

The Roman triumph was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory in the service of the state. The triumph concluded with sacrifices at the Temple of Jupiter on Capitoline Hill, where the commander offered tokens of victory and sacrificed two white oxen to Jupiter, dedicating the triumph to the Roman Senate, people, and gods.

The Roman triumph was a spectacular celebration parade and the highest honour bestowed upon a victorious military commander. Granted by the Senate, it was a lavish and entertaining propaganda spectacle that reminded the people of Rome's glory and military superiority. The triumph concluded with sacrifices at the Temple of Jupiter on Capitoline Hill, where the commander offered tokens of victory and sacrificed two white oxen to Jupiter, thus dedicating the triumph to the Roman Senate, people, and gods.

The day of the triumph was highly anticipated, with the general wearing a crown of laurel and an all-purple, gold-embroidered triumphal toga picta ("painted" toga), regalia that identified him as near-divine or near-kingly. In some accounts, his face was painted red, perhaps in imitation of Rome's highest and most powerful god, Jupiter. The general rode in a four-horse chariot through the streets of Rome in an unarmed procession with his army, captives, and the spoils of his war. The procession started outside the city in the Campus Martius and ended at the Temple of Jupiter on Capitoline Hill, where the conclusion of the triumph took place.

The sacrifices at the Temple of Jupiter were a crucial part of the Roman triumph. The general offered sacrifices and tokens of victory to Jupiter, the supreme deity of the Roman pantheon. This act of dedication concluded the triumph and served as a reminder that the commander was merely a mortal citizen who triumphed on behalf of Rome's Senate, people, and gods. The sacrifices and tokens were presented at the feet of Jupiter's statue, symbolically offering the victory to the gods and seeking their continued favour.

The Roman triumph was a highly elaborate and complex ceremony, with specific rituals and traditions that evolved over time. The conclusion of the triumph at the Temple of Jupiter was a significant aspect of this ceremony, emphasising the religious and ceremonial nature of the event. The sacrifices and offerings made to Jupiter were a way to honour the gods and seek their blessing for continued success and prosperity.

Almond Aroma: A Sweet, Subtle Fragrance Explained

You may want to see also