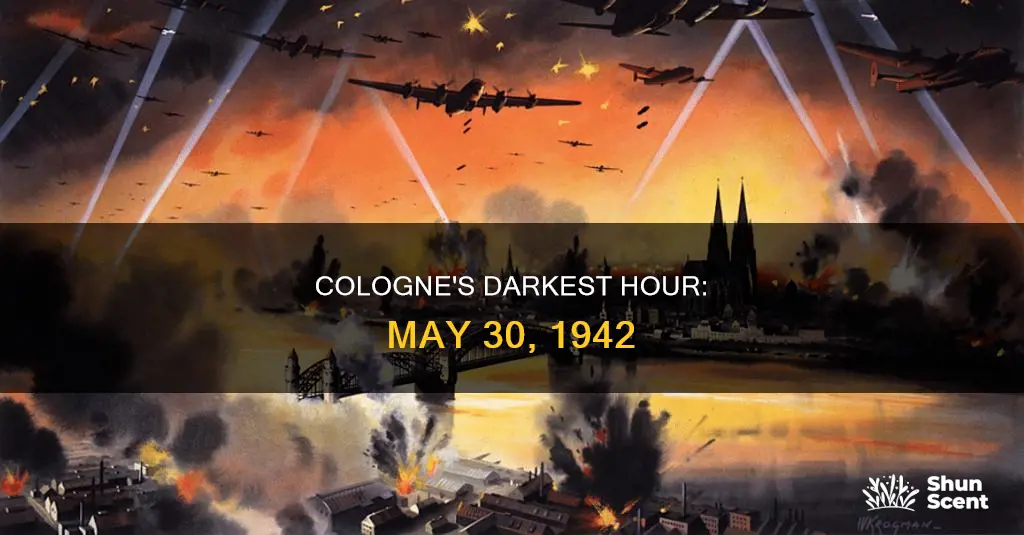

On the night of May 30, 1942, the German city of Cologne was subjected to a devastating bombing raid by the Royal Air Force (RAF). This marked the first of the RAF's 1,000-bomber attacks on Germany during World War II, aiming to cripple German morale and demonstrate the capabilities of Bomber Command.

The raid, known as Operation Millennium, saw 1,046-1,047 bombers drop approximately 1,500 metric tons of high-explosive and incendiary bombs on the city. The attack lasted for about an hour and a half, leaving 600 acres of Cologne in ruins, including 90% of the central city. The intense bombardment resulted in massive destruction, with 13,000 homes destroyed, 6,000 damaged, and 45,000 people displaced. The casualty count was significant, with 469-474 deaths and 5,000 wounded.

Despite the extensive damage, Cologne's iconic cathedral remained standing, boosting the morale of its citizens. The raid's overall impact, however, extended beyond the physical destruction. It signalled a shift in the war's strategic approach and prompted a response from Winston Churchill, who acknowledged the growing power of the British bomber force.

What You'll Learn

The first of the Royal Air Force's 1,000-bomber raids

On the night of May 30, 1942, the German city of Cologne was subjected to the first of the Royal Air Force's 1,000-bomber raids. Codenamed Operation Millennium, the raid was the brainchild of Air Marshall Arthur 'Bomber' Harris, who believed that heavy bomber attacks could win the war without the need for ground troops. Harris wanted to launch a devastating bombing raid on a German city, which would be so destructive that the German people would force their leaders to sue for peace. Harris dubbed this plan the 'Thousand Plan'.

Harris first discussed the Thousand Plan with Air Vice-Marshall Saundby in May 1942. After a few days of checking the numbers, Saundby informed Harris that the plan was feasible. At that time, Bomber Command comprised 37 medium and heavy bomber squadrons, giving Harris about 400 serviceable bombers—well below his target number of 1,000. However, by including Coastal Command and those bombers being replaced with new Lancaster bombers, Harris was able to get closer to his desired number.

The plan faced a number of challenges, including the risk of collisions and the need for decent nighttime weather. Harris passed these problems on to the experts, who found solutions. They estimated that there would be only one mid-air collision per hour if the raid was extended to 90 minutes and if the force had three separate targets within the city.

Harris received support for the plan from his superior, Charles Portal, Chief of the British Air Staff, as well as from Winston Churchill. The only dispute was over the intended target. Harris wanted to bomb Hamburg for its symbolic status, while Churchill favoured Essen as the heart of Germany's industrial might. However, scientists advised that Cologne would be the ideal target as it was within range for the use of the GEE navigation system and, as a major railway hub, its destruction could disrupt Germany's ability to move goods.

The raid was originally planned for the night of May 27-28, but it was delayed due to the Admiralty refusing to allow Coastal Command to participate, which reduced the number of bombers to 800. Harris made up the shortfall by using every available bomber, including those with pupil and instructor crews. On May 30, the weather conditions were favourable for a raid on Cologne, and Harris gave the order to start the operation.

A total of 1,046 bombers took off from 53 bases across Britain. The first bombers to arrive were the most modern, equipped with GEE navigational equipment—Stirlings and Wellingtons from 1 and 3 Groups. They had a specific target—the Neumarkt in the city's old town—which they were to set alight with incendiary bombs, creating a beacon for the other bombers. These planes would then bomb areas one mile north or south of the Neumarkt.

The bombers flew above the clouds from Holland to the German border, as predicted. When they reached Cologne, the moon gave the crews near-perfect visibility. Within 15 minutes of the first bombs landing, the old town was ablaze. The reaction of Cologne's civil defence force was slow, and only four bombers were lost in collisions over the city. The intensity of the attack was such that the final wave of bombers could see the glow of the flames from 100 miles away.

The raid resulted in the destruction of 600 acres of Cologne, including 90% of the central city. 5,000 fires were ignited, 3,300 homes were destroyed, and 45,000 people were left homeless. The casualty toll reached 474 killed and 5,000 wounded. However, the number of casualties would have been much higher if not for air-raid shelters and deep cellars under many homes.

Despite the extensive damage, Cologne was not destroyed. Industrial life around the city was paralysed for a week, but within six months it had recovered. Of the 1,046 bombers that took part, 39 were lost—primarily to night fighters—representing a loss of 4%, which was considered the maximum Bomber Command could sustain.

The raid demonstrated the growing power of the British bomber force and signalled Germany would face further attacks on its cities.

Creating a Unique Scent: Crafting Your Signature Cologne

You may want to see also

The Thousand-Bomber Raid

The raid was led by Air Marshal Arthur Harris, Commander-in-Chief of RAF Bomber Command, who advocated for the use of area bombing to destroy enemy morale through overwhelming attacks on civilian targets. Harris had to assemble bombers from various commands and training units to reach the desired number of 1,000 aircraft. In the end, about 900 bombers reached Cologne, dropping 1,455 tons of bombs on the city and causing massive destruction. The German figures reported 469 deaths, 45,000 people left homeless, and over 15,000 buildings destroyed or damaged, including 1,500 factories. The RAF lost 41 planes in the operation.

Exploring Men's Fragrances: Ordering Samples and Finding Your Scent

You may want to see also

Arthur 'Bomber' Harris' plan

On the night of May 30, 1942, the German city of Cologne was subjected to a large bombing attack by the British Royal Air Force (RAF), marking the first of the 262 air raids the city would endure during World War II. Codenamed Operation Millennium, this raid was the brainchild of Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur "Bomber" Harris, who commanded the RAF Bomber Command from 1942 to 1945. Harris was a staunch advocate of area bombing, also known as carpet bombing, which involved targeting German cities and industrial areas with massive aerial bombardments.

Harris's plan for Operation Millennium was bold and unprecedented. He intended to assemble a force of 1,000 bombers to attack Cologne, a feat that had never been attempted before. To reach this number, Harris had to scrape together bombers and crews from various sources, including operational training units, flying training command, and even pupil pilots and instructors. In the end, 1,047 bombers took part in the raid, with 868 aircraft bombing the main target and the rest targeting other locations.

The raid on Cologne commenced in the early hours of May 31, with bombers flying in a "bomber stream" formation to overwhelm German defences. Over the course of an hour and a half, the RAF dropped approximately 1,500 metric tons of high-explosive and incendiary bombs on the city. The results were devastating. Large parts of the city were flattened, with 90% of the central area destroyed. Some 2,500 buildings were completely destroyed, and thousands more were damaged. The raid caused massive fires, with German records indicating that 2,500 separate fires were started, 1,700 of which were classified as "large".

The human toll was also significant. Approximately 474 people were killed and 5,000 wounded, and 45,000 were left homeless. However, the death toll would have been much higher if not for the air-raid shelters and deep cellars that protected many residents.

From a strategic perspective, Operation Millennium had a mixed impact. On the one hand, it demonstrated the potential of large-scale bombing raids and boosted the morale of the British public and their allies. It also served as effective propaganda for Harris's concept of a Strategic Bombing Offensive. On the other hand, it did not achieve the primary goal of severely damaging German morale or knocking Germany out of the war. German propaganda at the time claimed that the British bombing would never break German morale, and indeed, the people of Cologne remained resilient in the face of devastation.

For Arthur "Bomber" Harris, Operation Millennium was a pivotal moment in his command of the RAF Bomber Command. It showcased his unwavering commitment to area bombing as a war-winning strategy and set a precedent for future bombing campaigns. Harris would go on to oversee more massive bombing raids on German cities, including the controversial bombing of Dresden in February 1945.

The Right Way to Dispose of Cologne Safely

You may want to see also

The use of GEE navigational equipment

GEE, or Gee, was a radio-navigation system used by the Royal Air Force during World War II. It was the first hyperbolic navigation system to be used operationally, entering service with RAF Bomber Command in 1942.

Gee was devised by Robert Dippy as a short-range blind-landing system to improve safety during night operations. However, it soon developed into a long-range, general navigation system. Gee was particularly useful for navigating to large, fixed targets, such as cities attacked at night. It offered enough accuracy to be used as an aiming reference without the need for a bombsight or other external references.

The system measured the time delay between two radio signals to produce a fix, with accuracy on the order of a few hundred meters at ranges up to about 350 miles. Gee remained an important part of the RAF's suite of navigation systems in the postwar era and was included in aircraft such as the English Electric Canberra and the V-bomber fleet.

The first operational mission using Gee took place on the night of 8/9 March 1942, when about 200 aircraft attacked Essen. The first completely successful Gee-led attack was carried out on 13/14 March 1942 against Cologne. The leading crews successfully illuminated the target with flares and incendiaries, and the bombing was generally accurate.

Gee was highly susceptible to jamming, and its usefulness as a bombing aid was reduced as a result. However, it remained in use as a navigational aid in the UK area throughout and after the war.

Does Nautica Cologne Change Color?

You may want to see also

The aftermath

The RAF's first "thousand-bomber raid" on the night of May 30, 1942, caused widespread devastation in Cologne. Around 600 acres of the city were flattened, including 90% of its centre, with 5,000 fires ignited, 13,000 homes destroyed, and 45,000 people left homeless. The casualty toll was 469 dead and 5,000 wounded. The attack had targeted residential areas, and the civilian population bore the brunt of the damage.

The raid's impact extended beyond physical destruction. Cologne's beloved Gothic cathedral, though damaged, remained standing amidst the ruins, a symbol of resilience that strengthened the morale of the city's inhabitants. The raid also had political repercussions, with Winston Churchill declaring:

> "This proof of the growing power of the British bomber force is also the herald of what Germany will receive, city by city, from now on."

The role of Bomber Command in World War Two remains controversial, with critics arguing that the heavy bombing of civilian areas constituted a war crime. However, supporters point to the strategic importance of these raids in ultimately defeating Nazi Germany.

In Cologne, the immediate aftermath was characterised by resilience and determination. The civil defence force, party officials, police, firefighters, and citizens all worked tirelessly to rescue those trapped under rubble, provide first aid to the wounded, and salvage belongings from damaged buildings. The city administration played a crucial role in restoring essential services, with temporary shops set up to provide food and other necessities. Despite the devastation, Cologne's industry was paralysed for only a week, and within six months, the city had largely recovered.

The RAF lost 39-44 aircraft in the raid, primarily to night fighters. This represented a loss of 3.9-4%, which was considered the maximum Bomber Command could sustain. The relatively low casualty rate, along with the significant damage inflicted, was touted as a success by the Allies, boosting morale and justifying their strategy of aerial bombardment.

Cologne Cathedral: A Survivor's Tale of WWII

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The bombing of Cologne was the first of the Royal Air Force's 1,000-bomber raids on Germany. It was expected that the devastation from such raids might be enough to knock Germany out of the war or at least severely damage German morale.

The raid lasted for an hour and a half, during which 1,500 metric tons of high-explosive and incendiary bombs were dropped. 600 acres of Cologne were flattened, including 90% of the central city, 5,000 fires were ignited, 3,300 homes were destroyed, and 45,000 people were left homeless. The casualty toll reached 474 killed and 5,000 wounded.

The German Luftwaffe claimed that they had avoided civilian targets, ignoring German attacks on Rotterdam and British cities.

The RAF lost 43 aircraft (German sources claimed 44), 3.9% of the 1,103 bombers sent on the raid.